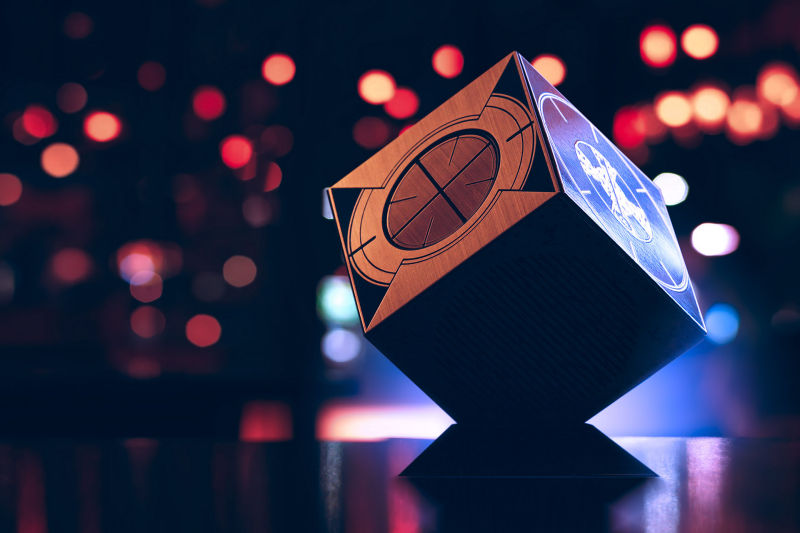

CAGE OF DESIRE

"The Dream Weave Cube"

Box art produced by William C. Johnson

Written research by Max Lichtor

Photo by Derek Prospero

"The Key to Catherine's Glory"

Catherine

II, Empress of

Russia

|

In

the year 1760, the Comte

de

Saint Germain was discovered as

a international spy by French

authorities. He fled France for England, where he stayed

for nearly two years in search of the LeMarchand box named Cage

of Desire - "The

Dream Weave Cube."

LeMarchand scholars believe that this particular configuration was

considered by the Comte to be the key that would unlock not only his

own

future, but the future of Czarist (Caesar's) Russia.

Immediately after aquiring the Cage of Desire from a collecter, the Comte de Saint Germain traveled to St. Petersburg. He played an important part in the revolution which placed Catherine the Great upon the throne of Russia. Catherine deposed her incompetent husband, Peter III, just six months into her rule. He was murdered less than two weeks later by the brother of her then current lover, Grigory Orlov. Catherine was known to have taken many lovers, but none were as close to her as Gregory Potemkin. He had contrived to make Catherine's acquaintance during the coup that brought her to power. |

|

|

Potemkin's name was a byword for gluttony, and he rarely woke before

noon. This was in sharp contrast to Catherine who rose at

three

in the morning to hunt and horseback ride, all the while "for 24 hours, eating

nothing

and drinking only cold water." Potemkin wooed the empress with what he called "The Key to Catherine's Glory." He claimed to have won the box from the Comte de Saint Germain during a night of gambling. Potemkin and Catherine became lovers in 1774. The couple's romantic relationship lasted less than three years, but they remained close the rest of their lives. He did not allow Catherine to touch the bronze inlaid box during these early years of their relationship. He only teased her with the sight of it, following their intimate moments together, all the while speaking dreamingly of their future destinies. |

| In 1783 Catherine annexed the Crimea after a war with Turkey, well aware that her new province was little more than "a desert waste." The Crimea must be transformed, she decided, and carefully considered those of her courtiers who might be able to carry out her wishes without much delay. Automatically she thought of Gregory Potemkin, who she had appointed to Assistant War Minister, and soon afterward Potemkin rose in rank to become War Minister. The promotion changed him from a gambling drunkard to Governor of the new Russian province. He was apparently inspired by Catherine's plans and so embarked on a whirlwind transformation of the Crimea. He noted all her plans, added many of his own, and started work without delay. |  |

He

began building

the harbor at Sevastopol and ordered

large fleets of battleships and merchantmen. From China, he

obtained silkworms and started a new industry. Forests and

vineyards sprang up in what had been virgin land. Most

impressive

of all, he produced plans for a grand new city on the River Dnieper

which he named Ekaterinoslav - "Catherine's Glory".

He

began building

the harbor at Sevastopol and ordered

large fleets of battleships and merchantmen. From China, he

obtained silkworms and started a new industry. Forests and

vineyards sprang up in what had been virgin land. Most

impressive

of all, he produced plans for a grand new city on the River Dnieper

which he named Ekaterinoslav - "Catherine's Glory".

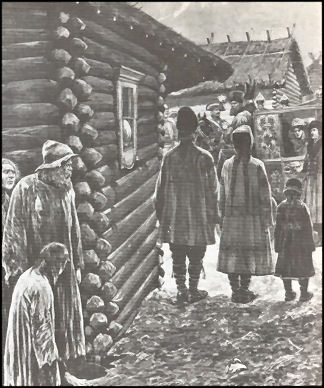

Over part of the route,

Catherine traveled with a retinue of 40,000

friends, officials and servants. Her sleigh was like a

miniature

house on runners and was drawn by eight horses. At each

stopping

place Potemkin had 500 horses stationed. Bonfires blazed at

scores of

points and every village through which Catherine passed had been

painted. To the empress everything was perfection - neat

houses,

happy villagers and a general air of contentment.

Over part of the route,

Catherine traveled with a retinue of 40,000

friends, officials and servants. Her sleigh was like a

miniature

house on runners and was drawn by eight horses. At each

stopping

place Potemkin had 500 horses stationed. Bonfires blazed at

scores of

points and every village through which Catherine passed had been

painted. To the empress everything was perfection - neat

houses,

happy villagers and a general air of contentment.